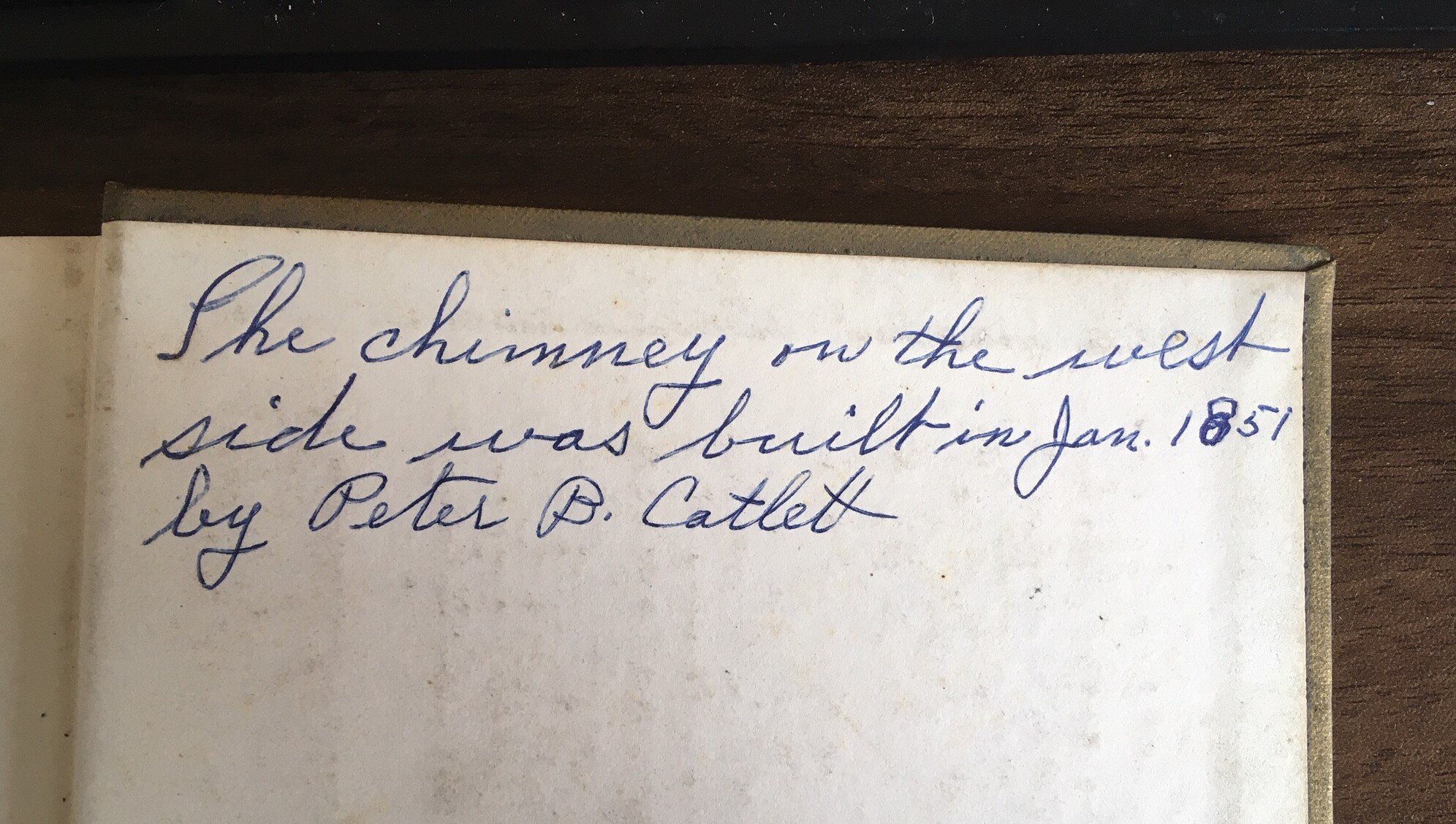

Awesome historical finds don’t just happen to Indiana Jones! This past week, while organizing our collection of artifacts, I happened to notice and pick up a cook book with an unusual title. Flipping through the book, I came across a handwritten inscription inside the back cover that read, “The chimney on the west side was built in Jan. 1851 by Peter B. Catlett”. Recognizing the handwriting as that of Sam Cockayne (1921-2001), the last member of the family to live in the historic farmhouse, I decided to do a little research on the seemingly random notation, starting with a quick Google search of the man mentioned, Peter B. Catlett.

As it turns out, Mr. Catlett was the son of one of the first settlers in Elizabethtown (which later merged with Moundsville), and seems to have resided in Marshall County most of his life.[1] His real claim to fame, however, was his involvement in the excavation of the Grave Creek Mound in 1838, and subsequently, his role in the Grave Creek Stone controversy.

In 1838, Jesse and Abelard Tomlinson led an archaeological excavation of the Grave Creek Mound. One of the most noted finds of this venture was a small stone with a series of unknown characters inscribed on its face. This small stone was destined to be the center of much debate. Throughout the nineteenth century (and into the twentieth, and into the twenty-first), archaeologists disputed the stone’s authenticity, some arguing that it provided evidence of a prehistoric American written alphabet, while others claimed that it was nothing more than a modern fraud. In 1879, J.H. Newton, writing his History of the Pan-handle, attempted to put forth all the evidence surrounding the stone and its discovery: “Much has been said and written about this stone, and it is the intention of the writer to submit the views and opinions of some of our most eminent archaeologists on the subject. What we want is truth, and the truth must in time prevail.”[2]

Though Newton was unsuccessful in definitively ending the debate, his chapter on the stone does include statements from many of the people involved in the original excavation, including Peter Catlett. Mr. Catlett’s letter is quoted as follows:

“May 6, 1876

Dr. P. P. Cherry:

Dear Sir – Your letter was received and contents noted. In the first place, I will say that I have been living in this place sixty-three years, and I know all about the mound alluded to from that date. In answer to the question, “Were you present at the opening of the mound?” will say that I was, and helped to do the work. Question: “Is there any other person or persons living at or near your place.” Answer: There are none. In answer to the third question, I will say that there was a stone in the mounds that had engraving on it. One side was filled with engraving, and about half filled on the other. I was the man who found the stone. [emphasis added] In answer to the question, “Was there a matrix, or, in other words, an impression of the stone where it lay?” I would say that the engraved stone was found in the inside of a stone arch that was found in the middle of the mound, and in that stone arch was found a skeleton that measured seven feet and four inches. When the bones were placed upon wires, I took the lower jawbone, and put it over my chin, and it did not touch my face, and I was at that time a man who weighed one hundred and eighty-one pounds. There were beside this skeleton some thousand of ivory beads, and five copper rings, two and a half inches in diameter, and about the thickness of a crayon pencil, and a lot of other things, such as stone pipes manufactured out of sandstone, but very neatly done. In regard to the nature of the soil all I can say is that the whole of the mounds is mixed with charcoal and bones, and on the top of the stone arch was found a skeleton of common size, and at the side of it there was charcoal the size of a man’s fist. From the appearance of the coals, and the quantity of them, it was intended to burn the skeleton, but was extinguished before it was burnt. In the stone arch alluded to there was no mechanical work. It was twenty-two feet in diameter, and we took the stone out, and put a frame in its place, and plastered it. AS FOR ANYONE PLACING THE INSCRIBED STONE THERE, IT COULD NOT HAVE BEEN DONE. We found that the other stone arch had a common-sized skeleton but very few trinkets in it. There are a great many other things that are connected with this mound that have slipped my memory, and I am so nervous that I cannot write. I owned a square lot about the centre of the town, that had two small mounds. They were about twenty feet high, and sixty feet in diameter. They were of coarse sand, and I made use of them for laying brick. [emphasis added] There were some trinkets in them, such as darts and tubes. The tubes were about fifteen inches long, and about one inch in diameter. They were neatly made, and as smooth as glass on the outside. I gave them to a man who came from New York, who belonged to the antiquarian society, and the version that he gave of them was that they were used as breathing tubes in times of danger, by hiding themselves in water. Col. William Alexander tells me that his wife has a copy of the diary of her grandfather, old Joseph Tomlinson, that man who first settled in the country, and who owned the mounds. I believe I have said all that is necessary to your questions. Hoping to hear from you again,

I remain yours,

P.B. Catlett”[3]

In this letter, Catlett identifies himself as the finder of the stone (though this is disputed by other accounts), making him a very important Marshall County character. His letter also confirms that he was in the business of laying bricks. Though a tragedy in many ways, it is nonetheless intriguing to think that some of the sand from those mounds may have ended up in the chimney of the Cockayne house. Even the world of history is a small one, and making these connections always seems like stumbling upon a secret treasure, even when such discoveries provoke as many questions as answers.

How did Sam Cockayne know that Mr. Catlett had built the chimney of his family’s farmhouse, long before his time? Was it simply a piece of family knowledge passed down to him? Why did he happen to write it down in the back of a cookbook?

Do any other examples of Mr. Catlett’s work survive in Glen Dale or Moundsville? If you know of any, please let us know!

Kara Gordon, Preserve WV AmeriCorps Member at Cockayne Farmstead

For more information on the Grave Creek Stone, see Wikipedia: Grave Creek Stone.

[1] Powell, Scott. The History of Marshall County (Moundsville, WV, 1925), 95-96.

[2] Newton, J.H. History of the Pan-handle: Being Historical Collections of the Counties of Ohio, Brooke, Marshall and Hancock, West Virginia ( J.A. Caldwell: Wheeling, WV, 1879), 366.

[3] Newton, History of the Pan-handle, 368-369.